UBC’s board of governors won’t be debating this at the upcoming public board meeting on December 5, 2024. I’m not sure the board ever will. In large part due to the fact UBC’s investments are managed by a private subsidiary of UBC and the process has them reporting to the subset of governors who sit on the finance committee.

The seven governors (out of twenty one) who decide are mostly business people and/or accountants (excepting the student governor). Under the streamlined procedures these are the seven people who vote on most of UBC fiscal maters. Only the really big things like the budget or tuition hikes come to the full board.

Back to UBC’s private investment firm. UBC Investment Management is a wholly owned private subsidiary of UBC. This puts it at arms length to UBC and not governed by the same freedom of information laws that UBC is. The opperational decisions on how the money is invested is placed even further away by essentially contracting out the decision making process:

UBC Investment Management does not make direct investments in traded securities — in other words, we don’t buy and sell individual company shares. Rather, we take a manager of managers approach, constructing portfolios by engaging top tier professional investment managers from around the world with specific expertise and proven records of performance who conduct security selection on our behalf. Our team works to select investment managers that we expect will generate superior risk-adjusted returns over time and have robust responsible investing practices integrated into their investment process.

What is UBCIM doing for ethical investments?

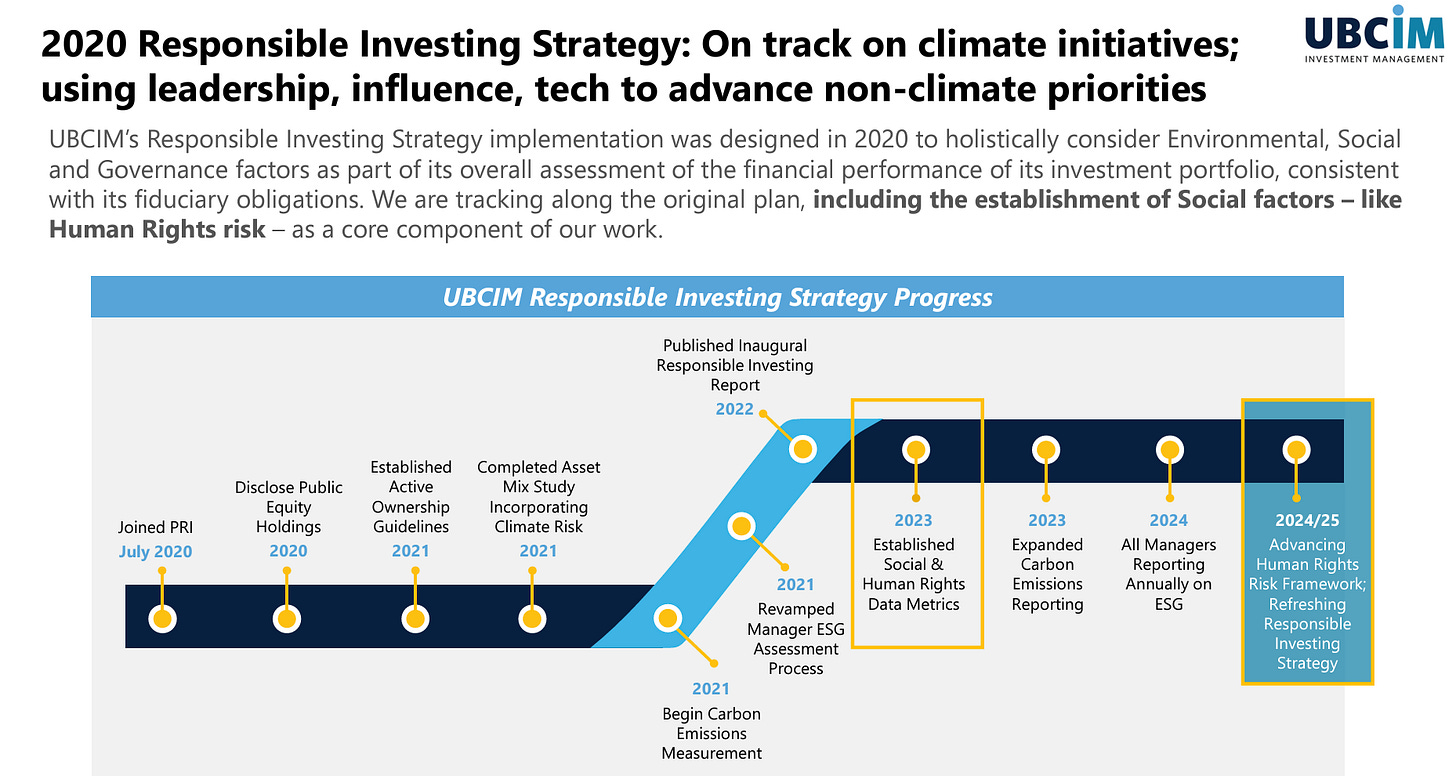

UBCIM presented to the Board Finance committee on November 20, 2024. Their presentation explained how they are hitting a variety of responsible investment targets.

The responsible investment strategy (RIS) was initiated in 2020 following a board decision to shift investments away from fossil fuels. While ‘ethical’ investing has a long history in financial markets, UBC’s approach didn’t explicitly highlight social concerns until 2020. Prior to this time the board had expressed concern with maintaining its fiduciary duties to donors who may not have considered ethical investments when they donated and, to their legislative responsibility to act in the best interests of the university (often defined conservatively as primarily fiscal interests). Following a non-violent, locally rooted, public campaign by members of the university community the board sought legal advice to work out a way to maintain commitments while considering social criteria for investment in addition to the standard economic ones. Thus arrived UBCIM’s 2020 responsible investment strategy.

UBCIM’s presentation to the board finance committee highlighted what has been done and pointed toward what was being done as they refresh the investment strategy given interest to include human rights concerns in investment decisions. Given the role of states like Russia (who faces direct legal sanctions), or China (with state owned companies now prohibited from engagement in certain sectors of the Canadian economy), or conflict zones i(n which economic investments may not support the objectives proponents claim they do), UBCIM has responded in a way they feel will provide “a comprehensive framework” for enhanced responsible investment.

What do the experts say?

There is an entire academic discipline parsing out the idea of ‘ethical,’ ‘socially responsible,’ and ‘impact’ investing. Most authors in the field are optimistic in their outlook for the potential of ethical capitalism. One analysis “argue[s] that the difference in performance between SRI [socially responsible investment] and conventional portfolios may, in fact, be insignificant due to the `mainstreaming’ of ethical investment.”1 This potentially puts to bed worries that being ‘ethical’ might cost investment earnings.

Ethical investing is not risk free for the companies involved. Ironically, being labeled favourably as an ethical firm is more likely to attract unwanted controversy: “business ethics controversies and regulatory issues are more likely for firms that disclose a richer set of ESG-friendly [environmental, social, governance] policies.”2

So while investors might not lose out on earnings by going ‘ethical,’ a company going ethical might face greater scrutiny and suffer ‘controversy risk.’

There is also a widely acknowledged ‘heterogeneity’ in terms, definitions, and approaches to ‘ethical’ investment. One paper reviews the variations, asks if standardization is useful, and offers suggestions for how this might happen. They summarize their explanations of heterogeneity as follows:

“There are at least three explanations which we think can account for the heterogeneity of SRI and, although we cannot fully determine their explanatory power, we think they raise interesting suggestions for future research. First of all, many terminological and practical differences may be explained by cultural and ideological differences between different regions. Furthermore, many strategic and practical differences can probably be explained by differences in values, norms and ideology between the many actors involved in the SRI process (the SRI stakeholders). An explanation which to some extent underpins these two, but which could also be considered independently explanatory, is the idea that the market setting in which SRI actors operate actually creates incentives for fund companies to develop terms, strategies and criteria slightly differently from their competitors.”3

One paper I particularly enjoyed asks if ethical investing is itself ethical.4

“Overall, there appears to be an implicit assumption by those connected with the social investment movement (e.g., ethical investment firms, individual investors, social investment organizations, academia, and the media), the ethical investment is in fact ethical.”

The author does a thorough review of the ‘ethnical’ screens used by fund managers. He concludes by observing that:

“if the ethical investing movement were to be honest and forthright, they would not label their screens as ‘ethical’ at all. They are simply screens developed with the intention of reflecting intended investors social, religious, or political attitudes or beliefs and nothing more.”

But is any investment ‘ethical’ or ultimately ‘responsible’?

In his highly regarded book, Red Skin, White Masks, UBC political scientist Glen Coulthard notes that capitalism is based on theft: a theft of time (extracting value from labour) and a theft of land (dispossessing original owners). This conceptualization of capitalism as theft unsettles any idea of ethical investment within capitalism.

I share an antipathy for capitalist enterprise given its track record in innovating inequality. If we are going to divest, maybe we should divest from capitalism writ large. Instead of playing the large capital markets what would it look like if UBC built social housing on its occupied territories instead of selling that right to developers. Rather than inviting in yet another private sector grocery store into Gateway North, what if UBC instead set up a food coop premised on cost recovery. I can already hear the arguments against this, but if we’re serious about having an impact with our investments why not start at home.

There are mid-way solutions that don’t require a radical departure from the market place.

Community Economies is one path:

“Community Economies is founded on the groundbreaking work of J.K. Gibson-Graham (the authorial voice of Katherine Gibson and the late Julie Graham). In publications such as The End of Capitalism (as we knew it): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy, A Postcapitalist Politics, and Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming our Communities, J.K. Gibson-Graham opened up our understanding of 'the economy' as comprised of diverse economic activities--including those are the basis for more ethical economies.”

“In the 1990s, the Community Economies Collective (CEC) was formed by J.K. Gibson-Graham and a group of scholars committed to theorizing, representing, and enacting new visions of economy. Members of the collective were mostly based in academic contexts in Australia, Europe, New Zealand and the US. Their action-research engagements were, however, spread across the globe.”

Elias Erragragui, Thomas Lagoarde-Segot, Solving the SRI puzzle? A note on the mainstreaming of ethical investment, Finance Research Letters, Volume 18, 2016, Pages 32-42, ISSN 1544-6123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2016.03.018.

Garvey, G. T., Kazdin, J., LaFond, R., Nash, J., & Safa, H. (2017). A pitfall in ethical investing: ESG disclosures reflect vulnerabilities, not virtues. Journal of Investment Management, 15(2), 51-64. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/pitfall-ethical-investing-esg-disclosures-reflect/docview/1934223839/se-2

Sandberg, J., Juravle, C., Hedesström, T. M., & Hamilton, I. (2009). The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment: JBE. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(4), 519-533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9956-0

Schwartz, M. S. (2003). The “Ethics” of Ethical Investing. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 195–213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25074989

It very much does depend on one's definition in my experience. I see a parallel in my recent work at UBC in medicine (having switched from science) which has a significant consideration of ethics before initiating the actual work of research. The parallel being a complete absence of any kind of meta-ethical critique process. What I see is essentially an appeal to authority in the form of law and nothing else. We should do far, far better at incorporating some sense of history and understanding just how terrible our system of law is at representing durable ethics. We have an opportunity to provide real value to the communities whose labour keeps us afloat. To provide a cultural investment in the future. To take our lives seriously and provide an inheritance with our time to those who come after us. Giving in to that one metric of value leaves so much behind.